|

300 H – THE FIRST OF THE LAST

By Gil Cunningham

Reprinted

from the 1974 Club News Volume II Number I

|

|

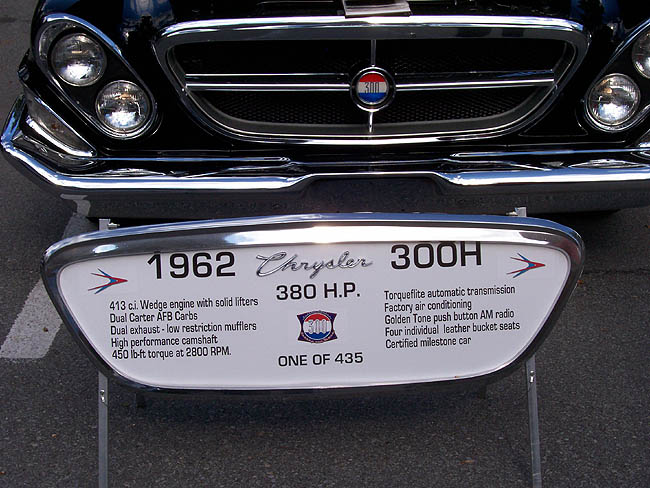

The year 1962 was a significant one for the

Chrysler 300 Letter Series automobile – albeit in a rather

negative sense. One aspect of this “negative significance”

is, in fact, implied in the wording of my first sentence. Prior to

1962 there would have been no need to clarify the 300 as a letter

series – the Chrysler 300 name plate had applied to only one

possible car.

Chrysler Corporation was not in good

financial shape in late 1961. They had weathered loss years in 1958

and 1959, and, after a reprieve in 1960, were sinking towards another

in 1961. Only well received 1962 model introduction in the fourth

quarter kept 1961 books in black ink.

Part of this successful 1962 model

acceptance was due to the introduction of an “additional”

Chrysler 300. In an effort to bolster sales by capitalizing on the

well-known 300 name, Chrysler dropped the mid-range Windsor series,

and replaced it with a sportier model called the “300.”

Marketing wise, this was a good decision and the “Windsor-300”

sold very well. Unfortunately, the dilution of the 300 nameplate

accompanied dilution of the letter series car itself. The 300-H

shared the shorter wheelbase body of the “300” and

Newport. In fact, it was virtually indistinguishable from the new

“300.” As a result, only 558 300-H automobiles (435

hardtop coupes and 123 convertibles) were built – the lowest

300 production to that date.

The most dramatic styling changes for

1962 were the rear quarters. Now devoid of fins, they in fact sloped

downward to the tail light. These new sculptured quarters were,

unfortunately, shared with the Dodge 880 of that year, and although

attractive, did have somewhat of a “tacked on” or late

“change of mind” look. This illusion may result because

the rest of the car was virtually unchanged from 1961.

The most dramatic styling changes for

1962 were the rear quarters. Now devoid of fins, they in fact sloped

downward to the tail light. These new sculptured quarters were,

unfortunately, shared with the Dodge 880 of that year, and although

attractive, did have somewhat of a “tacked on” or late

“change of mind” look. This illusion may result because

the rest of the car was virtually unchanged from 1961.

At any rate, Chrysler Corporation was

following the industry trend away from tail fins during the difficult

and more practical economic times of the early sixties. It might be

well to note here that these were the developmental stages of a basic

change in Chrysler philosophy to follow rather than lead, especially

in styling. This unfortunate policy has generally continued through

good and bad times to the present.

For the first time, the 300 was built

on the shorter 122” wheelbase, the 4 inch shortening occurring

forward of the doors. The resulting decreased hood length is perhaps

most noticeable from behind the wheel. For the restorer, however, the

change was probably beneficial since many more “short”

fenders would be available in junkyards than the longer New Yorker

units. 1961 Windsor and Newport fenders will also interchange.

Grille changes from 1961 were very

subtle, since the basic opening and canted headlight styling was

retained. The grille shell does not have the word Chrysler as it did

in 1961. The 1962 inner shell had a raised bead at its inner edge

around the opening and the cross ends were relieved to clear.

Therefore, a 1962 cross will fit in a 1961 shell, but not the

reverse. Grille background was also new, the 300-H utilizing a less

expensive expanded aluminum screen to replace the extruded assembly

in the 300-G. Last, but certainly not least, the grille medallion had

no letter under the 300 and was shared with the “Windsor-300.”

Grille changes from 1961 were very

subtle, since the basic opening and canted headlight styling was

retained. The grille shell does not have the word Chrysler as it did

in 1961. The 1962 inner shell had a raised bead at its inner edge

around the opening and the cross ends were relieved to clear.

Therefore, a 1962 cross will fit in a 1961 shell, but not the

reverse. Grille background was also new, the 300-H utilizing a less

expensive expanded aluminum screen to replace the extruded assembly

in the 300-G. Last, but certainly not least, the grille medallion had

no letter under the 300 and was shared with the “Windsor-300.”

From the exterior, there is only one

way, so far as I know, to tell a 300-H from the other “300”

– a small chrome “H” after the 300 on the deck lid.

The special 15” 300 wheelcovers are a good indication, but

these were used on non-letter 300s when ordered with the 380 HP

engine. Incidentally, for 1962, the color around their center

spinners was changed to black.

way, so far as I know, to tell a 300-H from the other “300”

– a small chrome “H” after the 300 on the deck lid.

The special 15” 300 wheelcovers are a good indication, but

these were used on non-letter 300s when ordered with the 380 HP

engine. Incidentally, for 1962, the color around their center

spinners was changed to black.

The 300-H was available in four solid

colors only, as shown below:

|

300H Exterior Colors

|

Code

|

Ditz No.

|

|

Oyster White

|

WW-1

|

8293

|

|

Formal Black

|

BB-1

|

9000

|

|

Festival Red

|

PP-1

|

71203

|

|

Carmel

|

ZZ-1

|

22095

|

Convertible tops were available in

either black or white.

As in previous years, a few 300-H’s

may have been special ordered in paint colors other than these. I

have not, however, seen any that could be verified.

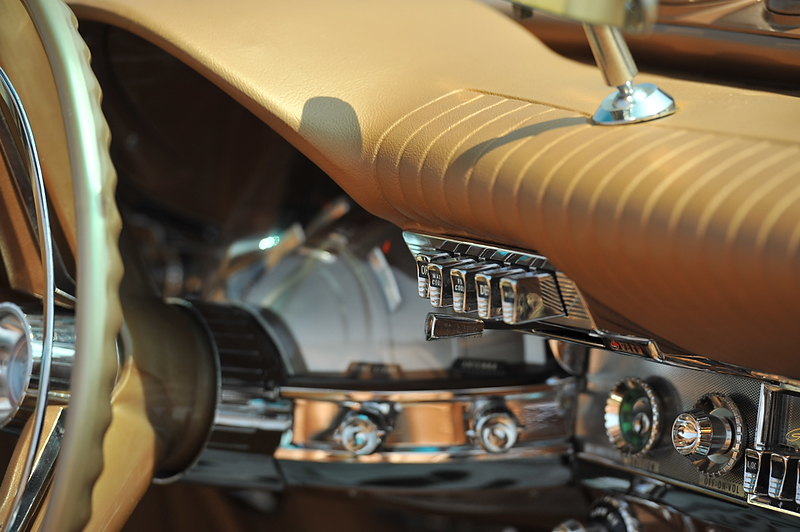

The 300-H continued the same basic

four individual seating design used in the F and G. There were

numerous interior changes however, many of which were intended to

reduce cost.

The entire interior was

now tan instead of the lighter beige used in 1961. Seats returned to

the 300-F pattern, but used more vinyl panels. Carpets were changed

from black to golden tan. The instrument panel was a metallic tan as

was the crash pad. Gone were the integral door arm rests of the F and

G. The “H” arm rests were conventional molded units which

attached to the door trim panels (which had embossed

piping yet!) by screws. Another foreboding interior change was the

replacement of the traditional 300 horn button medallion with one

incorporating the red, white, and blue colors around its

circumference. For those students of esoteria, the floor aluminum heel and

retaining plates had a different surface design than the F and G!

The entire interior was

now tan instead of the lighter beige used in 1961. Seats returned to

the 300-F pattern, but used more vinyl panels. Carpets were changed

from black to golden tan. The instrument panel was a metallic tan as

was the crash pad. Gone were the integral door arm rests of the F and

G. The “H” arm rests were conventional molded units which

attached to the door trim panels (which had embossed

piping yet!) by screws. Another foreboding interior change was the

replacement of the traditional 300 horn button medallion with one

incorporating the red, white, and blue colors around its

circumference. For those students of esoteria, the floor aluminum heel and

retaining plates had a different surface design than the F and G!

An interesting change in

the 300-H was the use of individually adjustable, but non-swiveling

front seats. Unfortunately, only manual adjustment was available, and

the versatility of a six or four-way power unit could not be

achieved. Power windows, steering, and brakes were standard, as

before. For the first time since 1959 auto pilot was optionally

available. In 1962 as in 1961 mirrormatic could be obtained only

as a dealer installed item.

I hope the preceding

paragraphs have not sounded like I might be “down” on the

300-H. I am not really (I own and enjoy an “H”

convertible); however the thought of what became of the 300 letter

series cars in succeeding years, starting in 1962, is always in the

back of ones mind, dampening the enthusiasm.

Fortunately, there is

one specific area of the 300-H where it may be impossible to be over

enthused – performance! Because of the 122” wheelbase,

the 300-H was around 10 percent lighter than an F or G which would

give it an acceleration edge with the same engine. But the standard

“H” engine was a higher winding slightly higher

horsepower unit. The long exotic rams were replaced with a

conventional in line 2-4 barrel carburetor arrangement, the cam was

wilder and the lifters were solid. The power plant was coupled to a

completely new aluminum cased Torqueflite which featured larger

diameter bands and planetary gear carriers, lighter weight, smaller

overall size (not too important in a 300-H with its console) and

manually controlled shifts when

desired (which was most of the time). But there was more for the lead

foot. Adding short rams (same overall length but siamesed inside) and

a wilder cam brought the 413’s horsepower up to 405 at 5400

RPM. This engine seems to have been available in the car from the

factory, but I cannot confirm this and have never seen such a

vehicle. One could go further, however. 1962 specifications list five

additional 426 cubic inch wedge head engines available through

Chrysler dealers for racing only, culminating with a 421 HP 498 ft

lb. torque macho job! The chart below will serve, it is hoped, to

clarify this maze of engine options: Fortunately, there is

one specific area of the 300-H where it may be impossible to be over

enthused – performance! Because of the 122” wheelbase,

the 300-H was around 10 percent lighter than an F or G which would

give it an acceleration edge with the same engine. But the standard

“H” engine was a higher winding slightly higher

horsepower unit. The long exotic rams were replaced with a

conventional in line 2-4 barrel carburetor arrangement, the cam was

wilder and the lifters were solid. The power plant was coupled to a

completely new aluminum cased Torqueflite which featured larger

diameter bands and planetary gear carriers, lighter weight, smaller

overall size (not too important in a 300-H with its console) and

manually controlled shifts when

desired (which was most of the time). But there was more for the lead

foot. Adding short rams (same overall length but siamesed inside) and

a wilder cam brought the 413’s horsepower up to 405 at 5400

RPM. This engine seems to have been available in the car from the

factory, but I cannot confirm this and have never seen such a

vehicle. One could go further, however. 1962 specifications list five

additional 426 cubic inch wedge head engines available through

Chrysler dealers for racing only, culminating with a 421 HP 498 ft

lb. torque macho job! The chart below will serve, it is hoped, to

clarify this maze of engine options:

|

Displacement

|

413

|

413

|

426

|

426

|

426

|

426

|

|

Horsepower @ RPM

|

380 @5200

|

405 @ 5400

|

373 @ 4800

|

385 @ 4800

|

413 @ 5400

|

421 @ 5400

|

|

Torque @ RPM

|

450 @ 3600

|

473 @ 3600

|

472 @ 3200

|

486 @ 3200

|

485 @ 3600

|

498 @ 3600

|

|

Comp. Ratio

|

10.1/1

|

11.0/1

|

11.0/1

|

12.0/1

|

11.0/1

|

12.0/1

|

|

Carb & Manifold

|

2-4 BBL Runner

|

2-4 BBL Ram

|

1-4 BBL ** Runner

|

1-4 BBL ** Runner

|

2-4 BBL Ram

|

2-4 BBL Ram

|

|

Intake duration

|

2680

|

2840

*

|

2920

|

2920

|

3080

|

3080

|

|

Exhaust duration

|

2680

|

2840

*

|

2920

|

2920

|

3080

|

3080

|

|

Overlap

|

480

|

550

*

|

670

|

670

|

880

|

880

|

|

Intake lift (zero

lash)

|

.444

|

.449

|

.490

|

.490

|

.520

|

.520

|

|

Exhaust lift

|

.456

|

.454

|

.490

|

.490

|

.520

|

.520

|

|

Exhaust valve

diameter

|

1.60

|

- 1.74 or optional

1.88 (stage III heads) -

|

|

Intake valve diameter

|

2.08

|

2.08

|

2.08

|

2.08

|

2.08

|

2.08

|

|

Carter Carb

|

F: AFB-3258-S

R:AFB-

3259-S

|

Two

AFB-3084-S

|

One

AFB-3397-S

|

One

AFB-3397-S

|

Two

AFB-3084-S

|

Two

AFB-3084-S

|

|

Transmission

|

3 Spd.

Man. or Torqueflite

|

3 Spd.

Man. or Torqueflite

|

3 Spd.

Man.

|

3 Spd.

Man.

|

3 Spd.

Man. or Torqueflite

|

3 Spd.

Man. or Torqueflite

|

*Later

production 405 HP engines used 2920 -

2920 - 670

cam

**NASCAR rules allowed

only one four barrel carb.

These engines were all available in the

“non-letter 300” and 300-H. When a non-letter was so

equipped 15 inch wheels with 300H wheelcovers and a 150 MPH

speedometer were included. I personally doubt that any 300-H was

built-up with a 426 engine – these would have been used in the

lighter “300” for racing purposes only. The 300-H, even

without 426 power, still possesses the distinction of being the most

powerful 300 ever available.

Performance of the standard 300-H was

exceptional, and the 405 HP job was fantastic. Hot Rod Magazine fine

tuned one of these 405 engines for drag racing and achieved runs as

low as 12.88 seconds elapsed time and 108 MPH.

All magazine road tests of the 300-H

lauded its performance, but I found it surprising that they also

praised its braking, since the brakes were the same 251 square inch

units as previous years.

Now, we all love our 300s, but most owners

of pre-1962 models will reluctantly admit not being too impressed

with the high speed performance of their brakes – not much room

between pedal and floor after that second 80 to 0 stop is there, old

chap? Oh well, I suppose even a Chrysler 300 must have at least one

minor deficiency. At any rate, the 300-H brakes had to stop around

440 less pounds than in 1961 and this apparently resulted in their

greater effectiveness.

Now, we all love our 300s, but most owners

of pre-1962 models will reluctantly admit not being too impressed

with the high speed performance of their brakes – not much room

between pedal and floor after that second 80 to 0 stop is there, old

chap? Oh well, I suppose even a Chrysler 300 must have at least one

minor deficiency. At any rate, the 300-H brakes had to stop around

440 less pounds than in 1961 and this apparently resulted in their

greater effectiveness.

The 300-H suspension was still firmer

than other Chryslers, but for the first time, not as much firmer.

Torsion bar rate at the wheel was 130 lbs. per inch as compared to

175 for the 300G. Rear spring rate was 125 lbs. per inch while the

300G springs were 130 to 140. It must be remembered, of course, that

because of its lighter weight, the 300-H would not require as high

spring rates for the same handling performance. The front anti-roll

bar was .75 inches in diameter, down from .82 on the “G”.

To complete the performance image the

“300” and 300-H were expected to uphold, 19 different

axle ratios were available, ranging from 2.76/1 to 6.17/1.

Any Chrysler 300 trivia

nuts among our readers will have a field day with the 300-H; highest

horsepower optional engine;, highest torque optional engine; most

engine options; most rear axle ratios, technically,

the first letter availability with a single four barrel (300K and L

owners take heart!); to list a few.

The possession of so many

esoteric “first” and “mosts” by the 300-H is

more understandable after one analyses conditions surrounding its

introduction. Chrysler may not have really known what to do with a

large super car in 1962. Compact and semi-compact cars with nearly as

powerful engines were just starting to emerge as the future

performance cars – and at a much cheaper cost. So, the 300-H

(and “300”) were provided enough options to enable them

to compete at the drags as well as NASCAR (in theory at least). So

far as I know very few hot Chryslers were campaigned in either event.

The new “B” body Plymouths and Dodges had less weight for

dragging and less wind resistance for top speed competition.

The possession of so many

esoteric “first” and “mosts” by the 300-H is

more understandable after one analyses conditions surrounding its

introduction. Chrysler may not have really known what to do with a

large super car in 1962. Compact and semi-compact cars with nearly as

powerful engines were just starting to emerge as the future

performance cars – and at a much cheaper cost. So, the 300-H

(and “300”) were provided enough options to enable them

to compete at the drags as well as NASCAR (in theory at least). So

far as I know very few hot Chryslers were campaigned in either event.

The new “B” body Plymouths and Dodges had less weight for

dragging and less wind resistance for top speed competition.

However, the 300-H, with its lighter

weight and 380 HP engine combining to form one of the greatest 300

letters ever, provided handling and highway cruising in the tradition

of its predecessors. And too, ownership of a 300-H is ownership of

the second rarest 300 hardtop or the rarest 300 model of all, the H

convertible. It is, of course, unfortunate that much of this fine

car’s identity was concealed in a standard appearing exterior.

However, as every 300-H owner or vanquished competitor is aware, the

only “standard” feature of the “H” was the

exterior!

|